Saving Grace

When he was growing up in New York, Victor Atkins didn’t imagine that he would become an artist. During the 1960s, there was a rise in drug related deaths in the Rockaway Beach, Queens community, a scene he didn’t want to become part of. “People were either overdosing or jumping off of buildings,” says Atkins, “and I didn’t want to do either of those things.” He pursed art school at the suggestion of a friend who was, “somebody who was doing something positive and creative away from all the death.” Art became a bright spot in that darkness, but only for a time.

While he hadn’t pictured himself becoming a painter, Atkins found success into his second year at School of the Arts. “It started very early,” he says of the gallery shows and recognition, “and I wish it didn’t.” Atkins chose to leave art school and focus on getting his work shown in more galleries. In later years, he would find that he had to work harder to make up for what he lacked in technical training. Still, his success rose.

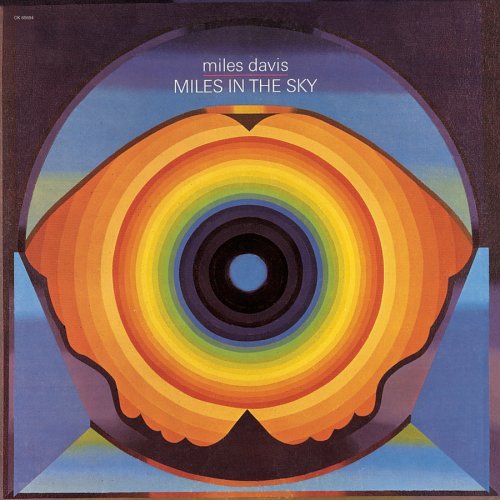

In 1969 Atkins would be awarded the Illustrator Award from the Society of Illustrators for designing the cover of Miles Davis’ “Miles in the Sky” LP. In the 70s, Atkins showed at galleries throughout New York City. He would paint until he faced some inner turmoil. With no spiritual anchor in his life, he says, “the thing that I saw in my spirit – I couldn’t come near it. It was too painful, too frustrating.” There was some distance between his vision and the canvas. “I could see something that I wanted to paint, and I couldn’t make it happen.” Atkins cites Jackson Pollock as an example of an artist “who saw something in himself that he couldn’t get out on canvas,” an experience that led Pollack to his death.

Atkins felt that there was no place where he could take his pain. He soon found himself drifting away from art. Painting began to feel like designing wallpaper. Prospective buyers seemed to go from purchasing his pieces as they were, to requesting reproductions with changes that would suit their taste. What was once freedom in painting turned into something else.

PS100

A group show at at Louis Meisel Gallery in 1978 would be Atkins last for more than twenty years. After a brief stint as a screen writer, he got married, opened a high-end bicycle shop, and lived a life based around the sport. Around 2000, he and his wife Diana would search for a fresh perspective by relocating to West Chester, Pennsylvania. They lived on wooded property, then moved around various counties while still running the bicycle business. Through a spiritual awakening, Atkins would find a bridge between himself and the inner struggle that distanced him from painting. As a Christian, Atkins was struck one night with a deep understanding that painting was what he needed to do. In this epiphany he felt that he needed to paint portraits, which he had never done. He resisted the strength of this message for months by hanging onto the reasons in front of him: their house was too small. There was no space for him to create his large works. He did not paint portraits. What would he do with the paintings? Overall, he really did not want to do it. Atkins would eventually share this experience with people who attended his church, and one of them would offer their well-lit spare room as a studio space.

In 2008 Atkins painted the series “Portraits of the Saints,” capturing images of people who were significant in he and Diana’s journey of faith. Diana insisted that portraits of people they knew would not sell. After the show at Providence Church in West Chester, Atkins chose to keep the portrait of her while all the others found new homes.

The Catch

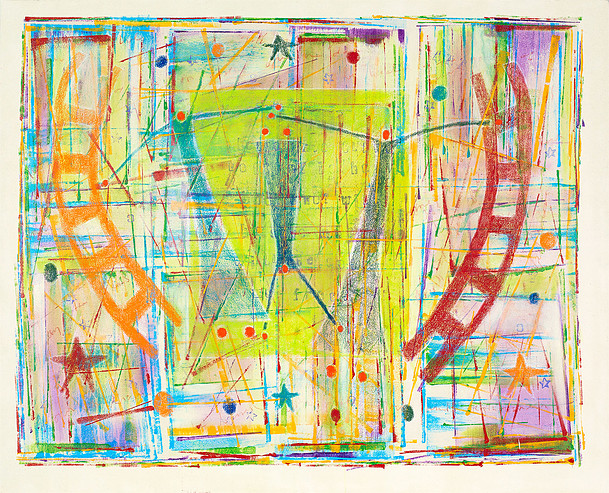

Interest started to grow in Atkins’ work, and the couple relocated to Philadelphia. The loft spaces in the city were large enough for Atkins to paint. He found his way back to his creative voice through collage, photography, and painting in a way that was both fun and challenging. He showed at Cairn University, White Stone Gallery among other group and solo exhibitions throughout the city. Their current home in Kensington is Atkins’ primary inspiration. The series “Angels Over Kensington” premiered at Legends Gallery in Fall of 2015. The images are of somewhat primitive patterns in bold colors, celestial shapes, suggestions of human figures, and various objects. Atkins wanted to represent the desire that he feels for spiritual awakening to enter a community where he sees desperation and destructive escapism.

“You can’t help but become affected by your environment. It becomes part of your DNA, it becomes what you think about, it becomes part of your body language,” says Atkins of the perceptive quality of a creative person’s existence. Atkins’ current series represents existing in the light of belief amongst darkness.

Come Sing Hallelujah

Atkins invites spectators into a sense of playfulness and joy in his large works. Each piece is around 70×90 inches and, in person, draws you into the colors and shapes. Symbols create sweeping gestures of emotion. In “Come, Sing Hallelujah,” figures have their arms raised, crossing over each other to create a sense of connection. Behind them, a circular shape the color of a golden morning sunrise seems to impart its hue on the spectrum of colors throughout the image.

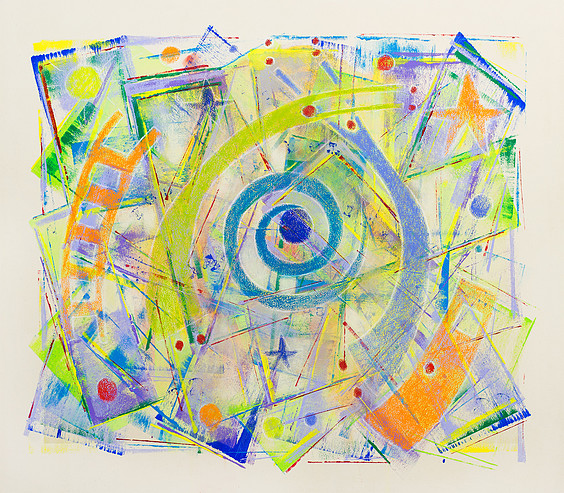

Being There

“Being There” layers blues and purples with bright yellow and orange. A blue spiral in the center is surrounded by two figures arching toward each other. They are framed by the curving shapes of a ladder and a door. Woven into the chaotic red, yellow, and green lines, the spiral and shades of blue throughout are a calm settling over and inside the frenzy.

It seems that Atkins has returned to the darkness that he witnessed at Rockaway Beach, and art is again a light. This time it isn’t an escape born from his own abilities, but a conscious decision to let the inspiration of spiritual wholeness fill his canvases. He sees the spiritual communion of painting as, “committing beauty back to the source of beauty.”

He is currently experimenting with the idea of creating an interactive installation using sound and sculpture also inspired by Kensington. While Atkins isn’t sure about what shape these ideas will take, he is ambitious and, most of all, inspired. He says that the spiritual engagement in his approach to art allows “things that I think I’m not capable of doing happen.”